INTRODUCTION

Theodor van Holst (1810-44) was an English Romantic artist who is perhaps best known today for being the first illustrator of Mary Shelley’s 1831 edition of Frankenstein. However from early on in his career, until his early death in 1844, he created work which anticipated and was much admired by members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. They felt a sympathy with his medievalism, draughtsmanship and colouring, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) in particular drew attention to Holst as a significant link between the older generation of painters such as Henry FuseIi (1741-1825), William Blake (1757-1827) and Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) and those who followed him. As well as Rossetti these included John Everett Millais (1829-96), Arthur Hughes (1832-1915), and the sculptor Alexander Munro (1825-71). Von Holst’s paintings such as The Wish (cat.41) and The Bride (cat.42) can be considered forerunners of the Pre-Raphaelite portraits of their ‘stunners’. These models and muses became overriding focal points in the lives and art of the PRB circle of artists. Holst’s painting The Wish also inspired Rossetti to write his first widely published poem, The Card Dealer, in 1848 and members of the Brotherhood frequented the London restaurant Campbell’s Scotch Stores in Beak Street because it was hung with paintings by Holst.

This bicentenary exhibition celebrates van Holst’s birth, explores his influence on the Pre-Raphaelites and acknowledges his debt to his earlier influences and teachers at the Royal Academy. Over fifty works are displayed, including one by Fuseli and two by Rossetti, and many of the paintings, drawings, books and letters are on show to the public for the first time.

The Holst Birthplace Museum would like to thank the following sponsors for their generosity which was essential for the realisation of this exhibition: Beechwood Shopping Centre; Cheltenham Arts Council; Cheltenham Surfacing Ltd; Cheltenham DFAS; West Mercia DFAS; The Charles Irving Charitable Trust; The Holst Foundation; Kingscott Dix (Cheltenham) Ltd; Nina Zborowska; Potter & Holmes Architects, and The Ernest Cook Trust.

HOLST’S ‘STUNNERS’

‘A most beautiful work by him – a female head or half figure

– among the pictures at Stafford House’.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1863

Nearly twenty years after Holst had died Rossetti recalled seeing Holst’s most famous painting, The Bride 1842, in the celebrated collection of the Duke of Sutherland at Stafford House. This picture clearly made an impression on Rossetti, and his painting Girl at a Lattice 1862 appears to have been influenced by it. The subject of Holst’s painting was Shelley’s 1821 poem, Ginevra, the tragic account of a young woman betrothed to an old nobleman she does not love and which results in her untimely demise immediately after the wedding. The sympathetic style and composition of The Bride recalls Italian Renaissance portraiture, as well as later derivations by the Dutch realists and the German Romantics. In this way it can be suggested that The Bride provides a link from the romanticized neo renaissance ideals of the German Nazarene school to that of the Pre-Raphaelites. Holst’s lone romanticised maidens lead to those by the PRB and particularly to Rossetti’s series of voluptuous ‘stunners.’

The Wish, painted a year before The Bride in 1841, adds to this link with its equally strong Pre-Raphaelite connections. This seminal painting provided Rossetti with the source for his first published poem The Card-Dealer: or Vingt-Et-Un. From A Picture. It is likely that Rossetti saw the painting atThirlestaineHouse, Cheltenham, then the seat of Lord Northwick, a renowned art collector, who had hung the painting prominently in his famous Picture Gallery (see illustration). In addition to inspiring Rossetti to write The Card-Dealer, The Wish also led to his large pencil drawing of The Card-Player and to Millais’s small but well known icononic painting of The Bridesmaid 1851. The voluptuous female figure in Holst’s The Wish may be based on the artist’s fiance, the twenty year-old Amelia Thomasina Symmes-Villard, whom he married in 1841 and whom according to William Bell Scott, was prone to jealousy and ‘… kept a stiletto secreted in the sacred hollow of her bodice for his benefit.’

The two early drawings by Rossetti displayed in this room usefully demonstrate his artistic and psychological empathy with Holst. La Belle Dame Sans Merci of 1848 is an early Rossetti ‘stunner’ and his first formal portrayal of a femme fatale, whilst his still earlier illustration of The Raven is a suitably menacing illustration of

Poe’s poem that reveals his taste for the macabre and supernatural and position as successor to the so-called ‘Satanic School’ of Fuseli and Holst.

Holst was just as capable of producing elegant portraiture as he was of enigmatic, mythic women. His Portrait of Jessy Harcourt 1837 (cat.38) who was the sister of Holst’s patron, John Rolls, demonstrates how successful Holst could be with a domestic subject. The rediscovery of this work in 2007 sheds further light on Holst’s oeuvre, and provides a tantalizing glimpse of his other recorded but now lost portraits which, it is hoped, will also emerge in time.

The Holst Birthplace Museum and Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum have a permanent collection of Theodor von Holst paintings, drawings and letters. Many of these items were donated by Imogen Holst, Gustav Holst’s daughter, when the Holst Birthplace Museum was established in 1975 and included Holst’s finest family portrait, Self-Portrait with Brother, Gustavus c1832-7. Gustavus was the first of the ‘Cheltenham Holsts’ – he moved to the town in the 1850s to teach young ladies harp and pianoforte. His son Adolph was the father of Gustavus Theodore von Holst – later known as the

composer Gustav Holst.

WORKS ON PAPER

Most of the drawings and watercolours by Theodor van Holst known today come from ‘The RollsAlbum’. This was a collection of some 300 works on paper, later mounted in a large album, which had been bought by Theodor’s patron John Rolls at Christie’s shortly after the death of the artist in 1844. Many of the more expensive and finer remaining works on paper at Holst’s sale were purchased by the collector and dealer Sergeant Ralph Thomas who was an early patron of Millais. Even by the time of Rossetti’s tribute to Holst in 1863 they seem to have disappeared and, unfortunately, still remain so.

Like the art of his masters, literary sources formed the basis of Holst’s work throughout his career: Shakespeare, Dante, Goethe, Motte Fouque, Lytton and Shelley all provided subjects for exhibition but by far the most important was Goethe’s masterwork Faust. Goethe (1749-1832) had popularised the legend of the ageing and disillusioned academic, Faust, and his pact with the Devil, to regain his youth, when he published his play name in 1808. Faust became a seminal source for artists, writers and intellectuals in the early 19th century, but Holst’s familiarity with German gave him a headstart and one with the advantage of the power of authenticity rather than translation. This tour-de-force of earthbound and supernatural forces continued to be Holst’s favourite source all his life.

Holst’s prodigious talent for drawing was recognised at an early age. When he was ten years old he sold a drawing to Sir Thomas Lawrence, President of the Royal Academy, who paid him three guineas for it. This event, at the British Museum, was set to open artistic doors for Holst and he became a student at the Royal Academy of Art four years later where he continued as a pupil of the eccentric Academician, Henry Fuseli, who was his earliest and strongest influence.

The works on paper are shown together with letters and ephemera associated with the Holst family, who originally came from Latvia. Matthias Holst (1769- 1845), a musician, left Latvia with his Russian wife Katherina and their young family around 1804. The items on display offer an invaluable insight into the family life and background of Theodor, who was the only one out of his three older sisters and brother to be born in London. It seems that Theodor and his brother Gustavus (1799-1870) were especially close and their joint letter to their parents, about a windswept walk from Eastbourne to Brighton (cat.2), truly brings their past vividly to life.

Gustavus was the first of the ‘Cheltenham Holsts’, and the grandfather of the composer, Gustav Holst (1874-1934)

LITERARY THEMES & FAMILY PORTRAITS

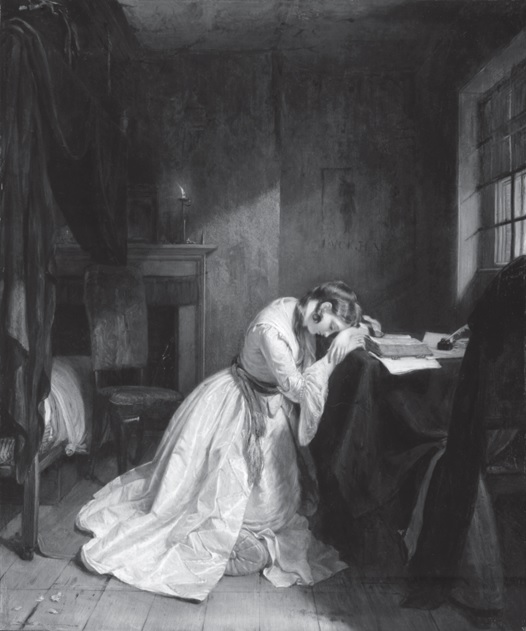

Henry Fuseli reportedly said that he, ‘… nearly wept everytime he read Clarissa Harlowe’, Samuel Richardson’s novel, which was published in 1748, to instruct young ladies in the art of letter writing. The tragic tale, of the virtuous Clarissa pursued by the villainous Lovelace, is still shocking in its depiction of forced imprisonment and sexual harassment. Perhaps Fuseli introduced Holst to the novel; what is clear is that Holst was familiar with Charles Landseer’s (1802-1873) 1833 Royal Academy painting of the same subject (see illustration) as there are obvious similarities between the former and the present version by Holst exhibited here. Holst’s Clarissa Harlowe in the Prison Room of the Sheriff’s Office (cat.35), may be a commissioned variant on Landseer’s composition for Holst’s patron John Rolls, since a picture of a Weeping Girl by the artist appears in the archives of the Rolls estate.

Apart from Sketches of Lady Macbeth with a Dagger and a Female Dancer, (cat.29) the literary sources for the other works displayed in this room are less obvious. The intriguing drawing, Young Woman Kneeling on a Cliff Edge Pleads to Flying Figures (cat.26) c1827-35 is influenced by the flying figures of Fuseli and William Blake (1757-1827), but its actual subject is unknown.

Holst’s interest in portraiture is represented in this room by his painting of his older sister Constantia (cat.4) and the two portraits of his nephew Gustavus Matthias, Portrait of a Young Child (cat.5) c1835, and Young Child Riding on a Model Dog (cat.6) c1837.

Constantia sat for him on numerous occasions and appears as Lilith and Gretchen in several sketches. Constantia seems to have been close to her brother and tellingly named her son Theodor after her brother’s early death. Gustavus Matthias (Gustav Holst’s uncle) who was born in 1833 grew up to be a musician, but also had a rebellious character. In Imogen Holst’s biography of her father (Gustav Holst, pp.4-5) Imogen relates how Gustavus Matthias was a talented and popular pianist, but: ‘Unfortunately his charm was not balanced by very much discretion, and after appearing at a fancy dress ball without any clothes on, an episode that reduced Cheltenham to a horrified silence, he was given a musical appointment in Glasgow and told that he need not come back.’