Meeting Imogen Holst in 1968

Geoffrey Poole

Imogen Holst led us from the Church of St. Peter and St. Paul, Aldeburgh, past increasingly tiny cottages and into her own. A small-framed spinster in her mid-sixties – this was June 1968 – Imo was quite a power-house, an indispensable Director of the Aldeburgh Festival, and interesting in everything she had to say. This had been evident from the outset, when we travelled from Snape to Aldeburgh in a minibus with Imo uncomplainingly wedged between her two current Hesse Student* helpers from the University of East Anglia, Peter Back and me. Someone observed that electricity pylons spoil the view of the tranquil fens. No such sentimental twaddle from Imo, who observed sharply, yet with a gleam, that you really wouldn’t want to be without the benefits of electricity would you?

Imogen Holst led us from the Church of St. Peter and St. Paul, Aldeburgh, past increasingly tiny cottages and into her own. A small-framed spinster in her mid-sixties – this was June 1968 – Imo was quite a power-house, an indispensable Director of the Aldeburgh Festival, and interesting in everything she had to say. This had been evident from the outset, when we travelled from Snape to Aldeburgh in a minibus with Imo uncomplainingly wedged between her two current Hesse Student* helpers from the University of East Anglia, Peter Back and me. Someone observed that electricity pylons spoil the view of the tranquil fens. No such sentimental twaddle from Imo, who observed sharply, yet with a gleam, that you really wouldn’t want to be without the benefits of electricity would you?

I did at one point watch her rehearsing an amateur women’s choir at the festival, and here too she demonstrated powerful communication, with a minimum of fuss. “Absolutely marvellous! Thank you, that was wonderful! (pause) I ju-ust wonder if – Contraltos, if you could bring out “in the Lord” on page 17, yes, just a little bit louder … and Sopranos, that top F sharp …” and so on. I couldn’t help thinking that her father must have been just like this, working up from the principle “A thing worth doing is worth doing badly” to “Now we can make it better!”.

The particular case that most impresses my memory concerned George Malcolm. Peter Back and I met Imo at the church at nine, to set up the rehearsal and performance space for his lunchtime harpsichord recital. There, somewhat surprisingly, Imo handed me pieces of card and a bold black pen, and instructed me to make six clear NO SMOKING signs. These she proceeded to place at the South door entry, and on the pews around the cleared pre-altar performance area. This seemed a strange thing to do in a church. Imo was happy to reveal her cunning plan: our virtuoso was a notorious chain-smoker. To this day I have seldom seen such imaginative ruses to ensure a compliance without risking confrontation.

At the end of an extraordinary week (for we had met Britten and Pears at the Red House, set up Orford Church amid rehearsal for all three Church Parables, attended the premiere of Birtwistle’s first opera Punch and Judy, and heard Maestro Rostropovich), here we were being served tea in Imo’s tiny kitchen, followed by admission to the inner sanctum, her small study, where the bulging stacks of material must have included her own compositions, drafts of her books, letters, festival administrative papers and conducting arrangements. But it was one of her father’s manuscripts that she lovingly laid out on the table. It was a neat pencil score entitled Double Concerto. Its solo violin and viola lines were respectively in two sharps and four flats. Extended bi-tonality of a sort, yet the accompaniment looked so sparse, there seemed to be insufficient harmonic basis to articulate the implied D-major / F minor tonal opposition of the melodic lines and (as indeed we can now hear on YouTube) this rarely-performed piece does seem torn between the duo’s quiet ‘alienated-pastoral’ inner world (this was the late 1920s) and the bravura of the orchestral bookends. Not perhaps as convincing as Egdon Heath, but certainly a unique and fascinating product of creative honesty, or as Holst writes to Vaughan Williams in 1926, the pursuit of “Dharma, which is one’s … clearly appointed path in life” whether successful or not – and there’s a powerful bit of encouragement to all who persist in the lunacy of composing from the soul.

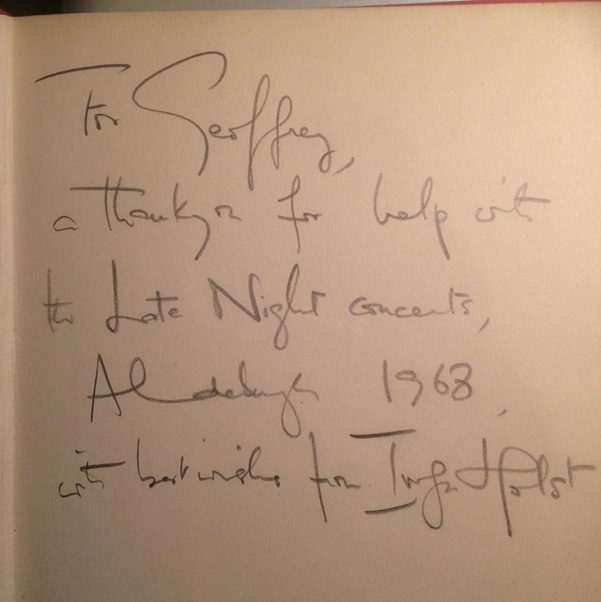

Finally, Imo made a present to each of us of a signed copy of a wonderful book that charts the development of the shared ideals of explorers Holst and Vaughan Williams, as documented by their letters and lectures. My copy of Heirs and Rebels remains the highlight of my library, and my encounter with Imogen Holst remains one of my happiest formative memories. Of course at 19, I could not begin to appreciate what Imo must have gone through in her own teens (as a Von Holst during a war against Germany), or the war’s destruction of the eligible husbands for her generation of women, or her extraordinary devotion to not one but two seminal geniuses of British music (and a great Festival). But even then, for me her “Miss Marple” qualities of personal modesty, shrewd judgement, immense capacity for industry, and her musico-social idealism shone out.

Her father would have been very proud.

Geoffrey Poole is the composer of music broadcast in 30 countries, pianist, and emeritus professor. He lives in Ruscombe near Stroud, and happens to share Holst’s interest in Asian cultures and a “weakness for astrology” – indeed he has lectured on Holst’s natal chart at the Isbourne Centre. He is currently recording a CD of his cycle of 64 I-Ching piano movements composed 2001-18.

* The Hesse Student Scheme for music students is run by Aldeburgh Festival.