This page contains several articles written by the late Graham Lockwood on the Holst family history and their contribution to music-making in Cheltenham in the 19th century. We are grateful to daughter Fiona Brice for her help in providing a tribute to Graham.

Graham’s professional career was as an actuary with Eagle Star Insurance, where he offered prizes for the Royal Overseas League’s music competition. Recitals were held in the gracious Eagle Star London office. When this ended he funded a prize at his own expense, an early example of his generosity which he later extended to the Cheltenham Music Festival. Graham was an enthusiastic amateur pianist.

After retirement he became deeply involved in the cultural life of Cheltenham where he eventually settled: first Director of the Cheltenham Music Festival (1993-99) and Chairman (2000-07); and Vice President of the Cheltenham Arts Festivals (2007). In 2008 he joined the Holst Birthplace Trust, becoming Chairman in 2010-14. He was also President of the Cheltenham Arts Council (2007-17) and all the while was involved with the Cheltenham Music Festival Society, the Cheltenham Music Society and the Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum Development Trust.

Somehow Graham found the time to research the history of music-making in Cheltenham and aspects of the Holst family in the town. His history of the Cheltenham Music Festival was published in 2009. Just before his death his acclaimed book Concordant Cheltenham: the making of a musical town 1716-194’ was published.

Meurig Bowen, a former Music Festival Director and HBT Trustee, perhaps summed up Graham best when he said that “In his quiet, thoughtful, diplomatic and determined way, Graham’s impact on Cheltenham’s cultural scene was immense”.

Gustav Holst was born at 4 Pittville Terrace in 1874 to Adolphus von Holst, a piano teacher and his wife Clara. Holst’s mother died in 1882 from heart disease when he was only eight years old.

Gustav Holst was born at 4 Pittville Terrace in 1874 to Adolphus von Holst, a piano teacher and his wife Clara. Holst’s mother died in 1882 from heart disease when he was only eight years old.

Holst and his little brother Emil were looked after by their aunt Nina, who along with his father, taught him how to play the piano and compose music. He attended Cheltenham Grammar School (now Pate’s Grammar School) and, when he was twenty one years old, he held his first concert at the Montpellier Rotunda (now Lloyds TSB).

Holst and his little brother Emil were looked after by their aunt Nina, who along with his father, taught him how to play the piano and compose music. He attended Cheltenham Grammar School (now Pate’s Grammar School) and, when he was twenty one years old, he held his first concert at the Montpellier Rotunda (now Lloyds TSB).

He then studied music composition at the Royal College of Music in London and became a music teacher at St Paul’s Girls’ School in London.

Whilst working as a music teacher, Holst wrote many pieces of music. His most famous collection of music was The Planets suite, written between 1914 and 1917.

This consisted of seven very different pieces of music, each representing the different ‘personalities’ of the planets. The most famous piece is Jupiter: Bringer of Jollity, a section of which is used as the theme for Rugby world cups.

Although he was unfit for military service in the First World War, in 1918 Holst joined the YMCA Education Department, helping to organise music activities in military training camps, hospitals and prisoner of war camps.  In order to avoid suspicion over his nationality, Holst agreed to drop the ‘von’ from his name, although he discovered that the family had never been entitled to it in the first place.

In order to avoid suspicion over his nationality, Holst agreed to drop the ‘von’ from his name, although he discovered that the family had never been entitled to it in the first place.

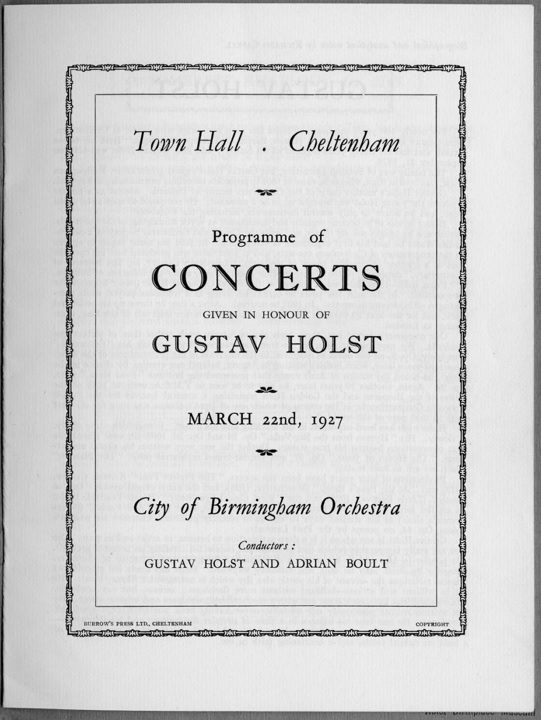

In 1927, Holst was honoured by his home town of Cheltenham with a two hour concert of his work, including The Planets, held in the Town Hall. Amongst the crowd were old school friends, violinists who had played with his father Adolphus and some very old ladies who had been taught music by his grandfather Gustavus.

In 1927, Holst was honoured by his home town of Cheltenham with a two hour concert of his work, including The Planets, held in the Town Hall. Amongst the crowd were old school friends, violinists who had played with his father Adolphus and some very old ladies who had been taught music by his grandfather Gustavus.

Holst continued to write teach and write music, although his health deteriorated in the last years of

his life. He died in 1934 at the age of fifty nine and his ashes were interred at Chichester Cathedral.

Clara Cox was the daughter of Mary Croft Whatley and Samuel Lediard of Cirencester. As the daughter of a solicitor, Clara would have grown up in relatively comfortable surroundings. She was taught to sing and play the piano. She was a gifted musician, playing and teaching the piano at Cranham parish church and giving piano recitals in Cheltenham.

Clara Cox was the daughter of Mary Croft Whatley and Samuel Lediard of Cirencester. As the daughter of a solicitor, Clara would have grown up in relatively comfortable surroundings. She was taught to sing and play the piano. She was a gifted musician, playing and teaching the piano at Cranham parish church and giving piano recitals in Cheltenham.

She attended Cheltenham Ladies College, where she met and married her piano teacher, Adolphus von Holst. They had two children, Gustav and Emil, who were both born at 4 Pittville Terrace. Clara managed the household whilst Adolphus travelled around Cheltenham giving piano lessons. However, Clara increasingly suffered from her ‘nerves’ during her marriage, forcing Adolphus to carry out his piano practice on a silent keyboard. Clara died of heart disease following a stillbirth.

Adolphus von Holst was born in 1846, the son of Gustavus von Holst and Honoria Gooderich of Cheltenham. As the son of a piano teacher and composer, Adolphus was taught how to play the piano from a young age. When he was an adult, he began teaching piano to the sons and daughters of the wealthy in Cheltenham, as part of their education. Adolphus was also an organist and conductor and played at both St. Paul’s and All Saints churches. He fell in love with Clara Cox Lediard, one of his pupils. They had two children, Gustav and Emil, before Clara died of heart disease.

Adolphus von Holst was born in 1846, the son of Gustavus von Holst and Honoria Gooderich of Cheltenham. As the son of a piano teacher and composer, Adolphus was taught how to play the piano from a young age. When he was an adult, he began teaching piano to the sons and daughters of the wealthy in Cheltenham, as part of their education. Adolphus was also an organist and conductor and played at both St. Paul’s and All Saints churches. He fell in love with Clara Cox Lediard, one of his pupils. They had two children, Gustav and Emil, before Clara died of heart disease.

After Clara’s death, Adolphus moved his family out of 4 Pittville Terrace and brought his sister Nina into his household to look after his children whilst he continued to work as a piano teacher. A couple of years later, Adolphus remarried and his sister no longer needed to live with him. Adolphus struggled with a drinking problem for much of his life and died in 1901 at the age of 55 after a drinking session at what is now Montpellier Wine Bar.

Emil von Holst was born at 4 Pittville Terrace in 1876. His parents were Adolphus von Holst and Clara Cox Lediard. He was the younger brother of Gustav von Holst.

Emil von Holst was born at 4 Pittville Terrace in 1876. His parents were Adolphus von Holst and Clara Cox Lediard. He was the younger brother of Gustav von Holst.

Emil enjoyed playing practical jokes on his older brother and would sometimes move the time on the clock back during Gustav’s hated violin practice, forcing him to practice for longer.

Emil attended Cheltenham Grammar School (now Pates Grammar School) and then went to work as a clerk in a wine-maker’s office before becoming an actor, at which point he adapted the stage name ‘Ernest Cossart’.

Emil acted on stage in Britain before moving to the US in 1908 and acting in shows on Broadway. He then moved into acting in Hollywood movies in the 1930s. He died in New York in 1951.

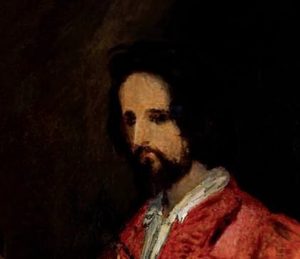

Theodor von Holst was the second son of Matthias Holst and Katherine Rogge, and was born in London in 1810. Theodor was a gifted artist and sold his first work at the age of 10. He went on to train at the Royal Academy of Art.

Theodor von Holst was the second son of Matthias Holst and Katherine Rogge, and was born in London in 1810. Theodor was a gifted artist and sold his first work at the age of 10. He went on to train at the Royal Academy of Art.

Theodor worked as a painter in London, producing many dark and mysterious paintings featuring mythical characters. However, in order to afford to live, Theodor also painted conventional portraits of wealthy people.

Theodor was extremely close to his older brother Gustavus and his sister Constantia, and the three often wrote joint letters to their parents. Theodor painted portraits of his brother and sister, including a self portrait with Gustavus.

Throughout his short life, Theodor struggled to find commercial success for his paintings. However, after his death from liver failure at the age of 33, a number of his paintings were permanently displayed in a restaurant in the West End of London. This restaurant was frequently visited by a group of young artists who admired von Holst’s paintings, and who went on to form The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, an important movement in nineteenth century art.

John Blacquiere was born in London in 1732 and started his career working in merchant’s office before joining the army in an Irish regiment. He had a successful career in the army and retired in 1773 to concentrate on his political career. He became a minister in the Irish House of Commons and, after the union between Britain and Ireland, he became a minister in the British House of Commons.

John Blacquiere was born in London in 1732 and started his career working in merchant’s office before joining the army in an Irish regiment. He had a successful career in the army and retired in 1773 to concentrate on his political career. He became a minister in the Irish House of Commons and, after the union between Britain and Ireland, he became a minister in the British House of Commons.

He was created Baron de Blacquiere of Ardkill, County Londonerry in 1800. He married an Irish heiress and had four sons and three daughters. However, whilst in the army, John had had an affair with a young actress called Caroline Ambrose, which had produced a son and a daughter, called Henrietta. Although the children were illegitimate, John provided for their futures, paying for his son’s education at Oxford and giving Henrietta £12 per year, although he did not publically acknowledge them as his children.

John’s political career made him rich, but he did give money back to the people. He gave a lot of money to Dublin, paying for the wide streets, paving and fountains that it has today.

Mary Croft Whatley was born in 1806 to David Whatley and Henrietta Ambrose. Being the daughter of a solicitor, Mary grew up in a fairly well-to-do household and would have received some education.

Mary Croft Whatley was born in 1806 to David Whatley and Henrietta Ambrose. Being the daughter of a solicitor, Mary grew up in a fairly well-to-do household and would have received some education.

When she was 20 years old, Mary married another solicitor, Samuel Lediard, with whom she had nine children between 1830 and 1847. Her

husband died suddenly of typhoid fever in 1852 when Mary was 46, and she was forced to look after her large family alone.

Mary moved to Cranham and then to Cheltenham so that her daughter Clara could attend Cheltenham Ladies College, and her son Henry Cheltenham College. They moved into 4 Pittville Terrace (now the Holst Birthplace Museum).

Mary moved to Cranham and then to Cheltenham so that her daughter Clara could attend Cheltenham Ladies College, and her son Henry Cheltenham College. They moved into 4 Pittville Terrace (now the Holst Birthplace Museum).

Mary was very religious, attending church regularly and frequently receiving visits from her local clergy. When Clara married Adolphus von Holst, Mary left 4 Pittville Terrace and moved to Cowley, near Oxford. She died in 1895.

Constantia von Holst was born in 1804. Her parents were Matthias Holst and Katherine Rogge, and her brothers were Gustavus and Theodor. Constantia had a very close relationship with her parents and brothers, which is shown in her letters. She also shared her family’s artistic talents and was a good singer – she hoped to train as a professional singer and become an actress.

Constantia also helped her brother Theodor by posing as a model in a number of his paintings – he also painted two portraits of her. However, her family did not have enough money to send her for any artistic training. She therefore secured her financial future by marrying a Professor of Languages, with whom she had four children.

Nothing more is known about Constantia’s life or her death.

Henrietta Ambrose was born in 1766, the daughter of John, Lord de Blacquiere and the actress Caroline Ambrose (1739-?). Her father asked two friends, Sir Richard Croft and Lord Denman to keep an eye on Henrietta and to help her if necessary.

Croft and Denman took their promise seriously and in 1773 took Henrietta away from her mother as they were concerned about Caroline’s respectability. Henrietta was sent to live with her father’s sister and her husband in Switzerland, but she returned to England when she was 16, where she became a governess. One of her pupils was a girl named Mary Spencer.

Years later, Mary Spencer was married to a solicitor in Cirencester called David Whatley. Dying, she asked Henrietta to visit her and made her promise to ‘take her place and become a mother to her child’.

A couple of years later in 1803, Henrietta married David Whatley and moved to Cirencester. Henrietta and David had a daughter whom they named Mary ‘Croft’ Whatley, after one of Henrietta’s guardians. Henrietta died in 1852.

Henry Lediard was born in 1847, the youngest son of Mary Croft Whatley and Samuel Lediard. Henry was only five years old when his father died of typhoid fever. After his widowed mother moved to Cheltenham, Henry attended Cheltenham College. A notebook from his days at the College is full of notes copied directly from the Bible, providing an indication of what school was like in the nineteenth century.

Henry Lediard was born in 1847, the youngest son of Mary Croft Whatley and Samuel Lediard. Henry was only five years old when his father died of typhoid fever. After his widowed mother moved to Cheltenham, Henry attended Cheltenham College. A notebook from his days at the College is full of notes copied directly from the Bible, providing an indication of what school was like in the nineteenth century.

Henry went to work with a GP in Monmouth for a year before going to Edinburgh University to study medicine. He then worked as a surgeon and physician (doctor) in Edinburgh.

Henry moved to Carlisle in the early 1880s, where he set up a doctor’s practice that he worked in until his retirement. Over the years Henry prospered. In 1881, Henry and his family had two servants and a groom. In 1901 they had three servants and a governess.

Henry died in 1932. The following year Gustav Holst, Henry’s nephew, travelled to Carlisle to conduct a concert in memory of his uncle.

Today Cheltenham basks in the fame that comes from being the town in which the composer of The Planets was born. The Holst Birthplace Museum attracts visitors from around the world and a near life-size sculpture of Gustav Holst now enhances Imperial Gardens in the town centre. For this the community must thank Gustav’s great grandfather, Matthias, born in Riga in 1769. It was Matthias who came to England and who was later to add the name of Holst to those contributing to Cheltenham’s growing musical tradition1.

This story began very early in the 19th century when Matthias Holst took the bold decision to give up his role as a professional musician attached to the Imperial Russian Court in St. Petersburg and, with his young family, to settle in London. Matthias’s talents equipped him to earn a living both as a composer and a teacher of playing the harp. His choice of London may have been influenced by stories of the financial successes of those continental musicians who visited or lived there. Haydn is reported to have accumulated 24,000 gulden from his two visits to England in the 1790s compared with just 2,000 gulden from his many years in the service of the Esterhazy family2. Handel had made a considerable fortune from his many years in London in the 18th century.

At that time the English were prepared to pay well for musical performance and tuition, but they also had their prejudices. Some of these probably derived from experiences of the Grand Tour in Continental Europe that was often part of the life of the wealthy young – what we may now consider as an up- market cultural gap year for the affluent. There was a passion for Italian opera in London with the accompanying perception that the best singers were also Italian – a prejudice that extended well into the 20th century.

Such lack of objectivity did not pass Cheltenham by. In 1840, having written an adulatory piece about a concert given in Cheltenham by an ensemble of Italian singers who, just a few weeks before, had been performing on the London opera stage, the reviewer of the Cheltenham Looker-On could not resist adding a jibe at their English counterparts who are ‘… by far, too apathetic: they may warble but they cannot be said to speak a language that will appeal to the feelings’3. It is not surprising that some English born singers adopted Italian stage names to enhance their career prospects. One such was Cheltenham born Conrad Boisragon who became known as Conrado Borrani on the London opera scene of the 1840s.

Alongside Italian singers, German musicians were also regarded well as instrumentalists. This must have helped Matthias Holst to become established in London but at some time in the late 1820s he strengthened his credentials further by adding the prefix ‘von’ to his surname. In so doing he may well have followed an initiative by his son Gustavus Valentine, who had inherited a talent for music and was also ambitious, seemingly aware at an early age of the marketing potential of such a German sounding name in those places where affluent pupils were to be found.

He judged rightly that Cheltenham was one such place. By 1832, Gustavus had become dissatisfied with the subservient life of a professional performer available on demand to patrons. He wanted a change of direction and Cheltenham, with its wide range of pleasure activities, alongside the health giving properties of its spa waters, seemed to offer this. Fashionable visitors were attracted in substantial numbers and the population of residents had increased significantly to over 20,000 including a doubling of the town’s female population over twenty years. If much of this increase can be explained by the rapid increase in demand for servants in the many new homes being built, it may well also reflect the reputation of Cheltenham as a place in which young ladies could enjoy a very active social life that would be enhanced by acquiring such desirable skills as singing and playing musical instruments. In this they were encouraged by performances in the town by the stars of the London opera stage and instrumental virtuosi such as Paganini and Olé Bull each of whom came to play twice in the 1830s.

Professional musicians for whom teaching was an important source of income had been attracted to the town since before the turn of the 19th century. Advertisements by those offering pianos for sale or hire, the sale of music scores as well as by those giving lessons in piano and harp playing, were already appearing in the 1810 editions of Cheltenham’s first newspaper, the Cheltenham Chronicle. However, even over twenty years later, the number of resident music teachers, many self-styled professors, was still modest. The first Cheltenham Annuaire of 1837 lists eight teachers of piano but only two for the harp. When Gustavus began to seek pupils through advertisements in the local newspapers from 1833 he offered tuition on the harp but later he offered piano lessons as well. He maintained a permanent London address because his time for teaching in Cheltenham was mainly in the high season of late summer when visitors came to participate in the lively social scene of the town after the ending of the London season.

Gustavus entered his newly chosen market at a good time and he did well. He began to appear as a harpist in the regular concerts of vocal and instrumental pieces performed by the local organists, teachers and other professional musicians. In one advertisement in November 1841 he was listed as a performer at a concert headed by the English singer Maria Hawes. This was at the Royal Old Wells .4 In the review of the concert a week later the writer was enthusiastic ‘As for Mr. Holst – he is decidedly one of the first harpists of the day – indeed one of the few who may be said to be effective on that very unmanageable instrument’5.

Sometime in the early 1850’s Gustavus moved his family home to Cheltenham, while keeping a London address. This was probably because of a new opportunity arising as a consequence of a changed social profile of the town. Powerful Evangelical preaching from the 1840s had ensured a dampened enthusiasm for party going. There was a shift in community ethos from pleasure to sobriety and education so pleasure seekers turned away from Cheltenham and towards the coastal resorts that had become accessible through the rapidly expanding railway network. Gustavus was adroit enough to take advantage of this change by accepting an appointment as one of the professors of the new Ladies’ College which opened in 18546. Music was one of the regular courses offered and extra lessons were available in music, as well as other subjects, at the rate of 5 guineas per half year. The senior school opened in February 1854 with over 100 pupils. Here his perceived, but mistaken, German origins continued to be advantageous. At Cheltenham Ladies’ College he was listed as Herr von Holst and he kept this appointment for a number of years while continuing to offer his talents as a Professor of Music both for individual tuition and for group classes at the Ladies’ College.

Gustavus died at 16 Cambray in June 1870 but by then his eldest son, named Matthias von Holst after his grandfather, had already established a presence on the local musical scene as a composer and successful pianist who seemingly enjoyed showing off his brilliance at the keyboard. He made an early public appearance. He was just eighteen when he played a solo on the harmonium in October 1852 at the Music Room at Hale’s, one of the town’s leading sellers of music and instruments. Under the patronage of the Duke of Beaufort the concert was intended to raise funds to enable a 13 year old piano student, Miss E Smith, to go to Australia. Sadly it was a sparsely attended event but Matthias had made his local debut7.

By 1858 he was placing advertisements in the local newspapers offering instruction in both piano and concertina, the latter having become popular as a parlour instrument for classical music after its introduction into the country in the 1830s .Later, when the harmonium also became popular in the home, he added that instrument to his tuition list. By 1863 both Matthias and his father were listed as professors offering lessons at 16 Rotunda Terrace in Cheltenham and that year, eleven years after his own debut appearance at Hale’s Music Room, Matthias provided a similar opportunity at that same venue, for his younger brother Adolph. At a concert on Wednesday 9 December 1863 Matthias played a solo on the piano in the first half and on the harmonium in the second. There were vocalists from Cheltenham’s Philharmonic Society and other instrumental works. Among these Adolph played the piano with an unnamed duo partner and this was reported as being the first public appearance of the seventeen old before a ‘large fashionable audience’8. So now there were three members of the von Holst family playing a musical role in the town.

But this period did not last long thanks to Matthias’s penchant for showing off. All seemed to go well for the next two or three years. One press review of a concert in December 1863 named him as one of four musicians each of whom ‘acquitted themselves in their respective performances greatly to the satisfaction of the audience which consisted almost entirely of ladies.’ Another well attended and well received event was billed as Matthias von Holst’s Annual Grand Concert. It was held in the Assembly Rooms on 9 February 1866 and had the support of the Philharmonic Society with the ‘celebrated English tenor, Tom Hohler, as soloist. Once more Matthias contributed some piano solos9 but according to his grandniece Imogen, at some point soon thereafter his apparent delight at appearing in public went beyond the concert platform and was to become a source of embarrassment to the family. Imogen records that the end came when Matthias decided that nudity was appropriate for one of Cheltenham‘s fancy dress parties10. This may have been family folklore but although Matthias did continue to appear listed alongside his father among the professors and teachers of music in the Cheltenham Annuaire until 1866 he then faded from the local scene. He died in Scotland in 1874.

After the departure of Matthias his father, Gustavus, was joined in the list just before he died, by a Miss Holst as a teacher of music. This was most likely his eldest daughter Catherine, known as Kate. She appears there again once more in 1870, but by now the family was also represented on the list by her younger brother, Adolph, who offered tuition in piano, organ and harmonium. He

was to stay on that list every year until the mid- 1890s.

Adolph(us) was born in 1846, the fourth child of Gustavus. He proved to be a very different person from his older brother Matthias. He took life much more seriously. He was hard on himself, his church choir and his musical son. After a period of study in Hamburg where his aunt Caroline was harpist to the Prussian court Adolph returned to Cheltenham. He soon became known as an exceptional pianist, teacher and conductor. He also became a notable church organist benefiting from the boom in church building which became a feature of Cheltenham during the later decades of the 19th century. He was first appointed as organist at St Paul’s Church for a year or so from 1865 and then as the first organist appointed at the new All Saints Church, consecrated in 1868. He was still just 21 years old but went on to hold that position for 27 years.

As a talented locally based musician he was fortunate that there were increasing opportunities to perform as the musical calendar of the town started to revive after the musically sparse summers of the 1850s and early 1860s. In the Holst Birthplace Museum is the scrapbook of programmes and press cuttings that Adolph compiled for most of the 1870s. Some entries suggest that he was in demand for private functions as well public concerts. There are two programme sheets for musical evenings at ‘Southam Delabere’ in January and November 1870, On those occasions the audience was entertained with a mix of solo and small ensemble singing, readings and piano solos from Adolph.

Among his regular pieces played here and elsewhere was Liszt’s showy Rigoletto paraphrase. Mendelssohn also featured regularly as did Schumann with Chopin and Weber less often. He also played duets with other instrumentalists especially with harpists and this provided opportunities to play compositions by his father Gustavus and uncle Matthias. Another piece he played in public frequently was Where the Bee Sucks by Benedict. This composer was also most certainly Sir Julius Benedict, composer, conductor and pianist who had been a student of Weber. One can only speculate that Adolph was among the audience at the Assembly Rooms when Sir Julius came to Cheltenham on 19 March 1874 to give a lecture, with musical illustrations, on ‘The Life of Weber.’

An unusually long gap in Adolph’s scrapbook occurred between February and September 1871. This might be explained by a change in his personal circumstances. In July that year, in All Saints Church, he was married to one of his pupils, Clara Lediard who was a singer, talented player of the piano in local concerts and of the harmonium in church. She was a daughter of solicitor Samuel Lediard whose family owned 4 Pittville Terrace, where the young von Holsts were allowed to live after their marriage. Their first child, a son, was born there on Monday 21 September 1874. He was christened at All Saints Church a month later with the name Gustavus Theodore. He is now known to all as Gustav Holst and the house in which he was born has become 4 Clarence Road, home of the Holst Birthplace Museum.

For Adolph that same year had begun with the last of his series of three Popular Classical Concerts which he promoted at the Corn Exchange from December 1873 to February 1874. This series was his first and he may have been inspired to arrange this by his experiences as a guest performer in a similar series in Gloucester the previous winter. The music in each of his concerts, played largely by the same small ensemble of musicians, would be familiar to Cheltenham’s chamber music audiences today; piano trios and string quartets by Beethoven, Haydn and Mendelssohn, and Schuman’s Piano Quintet. These were augmented by piano duets and solos in which Adolph played. The sketchy figures which Adolph scribbled in his scrapbook suggest a very small profit margin on the series but they must have been sufficiently appealing as he arranged another series the following winter. Moreover about this time the Montpellier Rotunda received some restoration. It became, for Adolph, a regular venue for nearly twenty years playing there in concerts that he arranged either on his own initiative or on behalf of others and making guest appearances such as those with the local string quartet. He also arranged works for the musical resources available. One example is a Rotunda concert on 26 November 1872 when a Mozart Symphony in C was played in his arrangement for harp, violin, flute, cello and piano. In this way he was able to introduce new repertoire to local audiences.

There is another example of this five years later by which time he was now one of the town’s leading professional musicians. Proudly mounted into his scrapbook are both the programme and the subsequent press comment on the concert he presented at the Assembly Rooms on 10 February 1877. This attracted more than usual attention for two quite unrelated reasons. The music performed included songs and a major piano trio composed by Franz Schubert in the last year of his life (a work identified then as Op 99 in B Flat and now known as D. 898). The performance of compositions from forty years or so earlier might not now seem particularly adventurous but it had taken many years for the music of Schubert to become widely appreciated. Only about half of his compositions had appeared in print by the 1870s so Adolph’s choice of music to be played was relatively unusual in the provinces at that time.

The Cheltenham Looker – On of 17 February 1877 considered the concert as being ‘specifically addressed to the musically educated’ and which only accomplished artists could perform. The Cheltenham Examiner of 14 February went further. The columnist wrote: ‘Perhaps the beautiful trio with which the concert opened was found too long by the some of the audience ….but it should be remembered that when first rate artists are brought down from town they will play music not only of the highest class but having a claim to novelty; probably this trio of Schubert’s has not been done at a Cheltenham concert before’.

The second cause for public reaction must have been a surprise for Adolph. One of the songs was Die Junge Nonne – a story of a young nun. An audience member reached for his pen and write to the Cheltenham Chronicle. Adolph pasted into his scrapbook the letter which expressed outrage and accused the concert promoters of deviously insinuating Popery into the town. Fortunately another correspondent wrote a robust defence of Adolph and his efforts to introduce high quality music to Cheltenham. Naturally this too is pasted in the scrapbook.

Recognition of his local standing at that time came with the opening of the new Winter Garden on the afternoon of Wednesday 8 November 1878. Lord Fitzhardinge performed the opening ceremony after which there was a concert. Adolph played Mendlessohn’s Piano Concerto op 40 with an orchestra ensemble, a sparkling work which would have been appropriate to the occasion and a good showpiece for the pianist. His popularity at that time is further evidenced by his scrapbook collection which shows that in almost every month of 1879 he continued to perform in Cheltenham and around the country as well as being busy as an organist and teacher.

The surviving scrapbooks cease at the end of 1879 but it is clear that throughout the following decade and into the early 1890s Adolph continued his own well regarded musical life in Cheltenham where the musical scene continued to be vibrant. A glance through the local advertisements for concerts in the first half of the 1890s shows just how much was going on. In a variety of venues there were concerts given by local amateurs, resident teachers and especially by renowned visiting artists such as the piano virtuosi Paderewski, Moriz Rosenthal, Emil Sauer and the 17 year old prodigy Josef Hofmann, pupil of Rubenstein and then at the threshold of a remarkable international career. A young Clara Butt appeared as a junior member of an ensemble of visiting singers. The Hallé Orchestra under their founder Sir Charles gave two concerts in the Winter Garden. But amidst this visiting talent Adolph continued to perform to local acclaim. His most regular public engagements were as the resident pianist in subscription concerts in the Montpellier Rotunda arranged by local musician Peter Jones during the four years from 1891.Each series of twelve weekly concerts took place in the afternoons starting in late autumn and attracted audiences upwards of two hundred. Peter Jones put together an ensemble of perhaps a dozen instrumentalists which he advertised as his orchestral band.

With such resources Adolph could also introduce the audience to compositions for piano and orchestra, usually arranged for the smaller ensemble of musicians available. Piano concertos were not otherwise a regularly featured in Cheltenham at that time and so the adapted versions played in those afternoon series proved to be popular. In January 1892 he was praised for the quality of his playing of the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto in C and especially the cadenza he composed for it11. This was probably the first concerto in C major. Later reports noted a performance of a Fantasia for piano and orchestra by Liszt which would have given Adolph a chance to show off his formidable technique as well as introducing a composition not previously heard in the town. He also played solo piano works during these afternoon concerts with Beethoven, Weber and Saint-Saëns featuring and he took opportunities to display the talent of some of his pupils by playing duets with them. In one concert he introduced his pupil, Miss Falcon, and together they played Bach’s Concerto for two pianos and orchestra and a Mozart Fantasia in C minor to which a second part had been added by Grieg.

But behind this story of continuing public success there were significant changes in Adolph’s personal circumstances. His wife Clara had died in February 1882 leaving him not just a widower but the father of their two sons. As his granddaughter Imogen wrote much later, they were left ‘…to the tender mercies of a father who practiced all the time he was at home, and whose dream of domestic happiness was to live on the top floor of a well-run hotel.’12 But Adolph must have spent considerable time with the young Gustav(us) who was showing precocious talent at the piano. Adolph taught him technique and repertoire with the aim that he should become a concert pianist. Gustav was good enough to appear at a public performance by the age of 16. At a Saturday afternoon concert in the Montpellier Rotunda on 13 December 1890 he played a piano duet with his father.13 Just a few days later took an active part in a concert following a prize giving event at the Cheltenham Grammar School where he was a pupil14.

As he came to the end of his school days Gustav contributed to the town’s musical life in a number of ways. He assisted his father at All Saints Church. He was a choral singer and instrumentalist there but all this time he was developing a talent and strong preference for musical composition. Anyone slipping quietly into All Saints Church at this time might have heard the sound of young Gustav trying out his own organ voluntaries and other compositions on the church organ. This would not be when his father was around because, at that stage, Adolph did not look favourably on the idea of Gustav being a composer. Instead he continued to urge hard practice at the keyboard to ensure a career as a concert pianist.

Gustav helped his father with the administration of some of the regular Saturday afternoon chamber music performances which Adolph helped to arrange at the Montpelier Rotunda. During one such concert Gustav joined his father on the concert platform and they played a Mendelssohn piano duet together. He was also rewarded by having some of his own compositions played. There was a performance of his Scherzo for small orchestra on Wednesday 16 December 1891 followed just four days later by an Intermezzo. Another week later, on Boxing Day, a song of his was included in the concert that afternoon.

The tide of Gustav’s future began to turn significantly the following year just after he had left school. It was a year in which he expanded his musical horizons. He went to opera performances in London and became influenced by Wagner and Sullivan. He studied counterpoint for several weeks in Oxford15. He took his first step as a professional musician by becoming the modestly paid organist and choirmaster at Wyck Rissington Church. He also had a short experience as conductor of the Bourton-on-the-Water Choral Society when they sang an oratorio. The benefits of these experiences influenced Holst’s formative years as a composer.

For Cheltenham concert goers the highlight of the second week of February 1893 was a return visit by the famous violin virtuoso Pablo Sarasate. He attracted a capacity audience at the Assembly Rooms on the Wednesday afternoon of 8 February. That concert was promoted by Dale Forty the renowned local piano firm and Frank Forty of that partnership was also Gustav’s godfather. He therefore surely took a personal interest in the event across the road in the Corn Exchange the previous day – an occasion which was to prove to be of long lasting significance. There the audience had witnessed the first of the performances of the comic opera, Lansdown Castle or The Sorcerer of Tewkesbury, sung to the music of Gustav Holst that he set to words by Major Cunningham. The plot, such as it was, was set in the reign of Henry VII. Some selections from the work had been sung in one of the musical afternoons of late 1892 but the first full performances were now given by an amateur cast on the afternoon of Tuesday 7 February and the evening of the next day. The plot of the opera was all somewhat inconsequential but the music provided variety and enjoyment for the audiences.

Imogen Holst records that after this ‘Even Adolph was impressed. He borrowed a hundred pounds from one of his relations, and sent Gustav as a student to the Royal College of Music’16. Gustav left Cheltenham for London that same year. He returned regularly but such visits were mainly family affairs. However in Imogen Holst’s catalogue of all her father’s works17 it is recorded that Adolph and Gustav gave the first performance of Gustav’s unpublished Duet in D for two pianos at a concert at the Rotunda on 13 May 1899. It was to be another twenty eight years before he was to return to a concert platform of the Town Hall at a triumphant civic event in his honour.

After Gustav had left for London Adolph continued, for a while, to perform in public concerts. As well as the afternoon series in the Montpelier Rotunda there were other engagements. In the early part of the 1890s he played again with the Cheltenham Quartet Society in some of their chamber music concerts. The first few months of 1895 also saw him performing at the keyboard in different concerts and venues. In early May he played a benefit concert arranged for his regular music associate Peter Jones. On this occasion Adolph was described as having bravely put his reputation on the line by performing a work for piano and orchestra by Raff and called simply Minuetto. The reviewer called it the pièce de résistance of the evening18. On another occasion that month he showed some pride in the emerging composing talents of his son when, within the framework of an organ recital in Highbury Congregational Church on 8 May 1895, Adolph included the first performance of a Duet for Organ and Trombone composed by Gustav. James Boyce was the trombone player on that occasion.

He was again bold at a benefit concert for Jones in February 1896 when he dominated the programme with Beethoven’s Choral Fantasia for piano, chorus and orchestra and Sterndale Bennett’s Caprice for piano and orchestra. Other engagements that year included appearing as soloist with the Ladies Choir under the direction of local singing professor, Herr Lortzing, and at the Annual Benefit Concert of the Town Band in March 1896. But Adolph was now near the end of his playing career and it is fitting that one of his final recitals in the town was also his most ambitious. It was programmed in October 1896 and advertised as a full piano recital with some orchestral accompaniment. It was in his regular venue, the Montpellier Rotunda, and he performed a testing recital of pieces by Liszt, Chopin, Rubenstein and John Field. He received praise for his playing and for the ‘distribution of programmes containing the principal musical themes.’19

In January 1895, while still only fifty years old, he had retired from his position as organist and choir master at All Saints Church. He was given a handsome testimonial and a sum of 63 guineas from the grateful Vicar and Churchwardens20 but he had lost a steady source of income. Furthermore Mr. Jones appears not to have promoted another autumn series in late 1896 and Adolph was no longer the principal guest pianist of the local string quartet. From that time onward his story was a sorry one. The benefit money from All Saints may have been useful in repaying some of the family debt he had incurred when sending young Gustav off to Music College, or he may have spent it unwisely. Adolph’s second wife had left for America taking their two sons with her and, at some point after that duet with Gustav in 1899 Adolph broke his wrist and could no longer play. He died in August 1901. The Cheltenham looker-On which had so often written favourably about his public performances recorded an obituary in its edition of 24 August. It began:

Mr. Adolph von Holst’s sudden death last Saturday from apoplexy removes from our midst a gentleman who has been for a great number of years one of the most prominent and talented local musical professors.

And with admirable prescience the obituary concluded

His eldest son by his first wife, Gustav von Holst, is showing great promise as a composer.

By poignant coincidence, within a few days of Adolph’s death, two concerts were given in Cheltenham by the White Viennese Band, one of the bands with which young Gustav Holst had, until 1898, played the trombone regularly to earn money while studying at the Royal College. Gustav was later to recall that although half of the White Viennese Band was British they were asked to speak with a foreign accent when near the public. ‘It was understood that if you were a good musician you must be a foreigner’21 Sensibly, he adopted his own father’s practice of prefixing his surname with ‘von’ until it became such a disadvantage during the years of the First World War that he changed his name back to plain Holst in 1918.

It was of course fortuitous that Gustav’s decision to forego the ‘von’ came at about the time that the composition that was to bring him fame received its first hearing, at least in part. This was a private performance of five of the seven movements of The Planets. Within a few years the sound of that music and the name of the composer had achieved international recognition. Until then the townsfolk of Cheltenham had probably largely forgotten the Holst name as it had been more than twenty years since Adolph last performed locally and even longer since Gustav had gone away to study. But with his new fame in the 1920’s Gustav was quickly claimed as a son of the town. Some of its leading citizens determined to mark this success and their initiative was to lead to the last appearances of a Holst on the Cheltenham concert platform. The first, in 1927, was a celebration with two performances of his music in the Town Hall with Gustav himself conducting The Planets.

Such was the pleasure he gained from this mini-festival of his music and the plaudits of the town, that he returned to the Town Hall the following year to conduct the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra in the British premiere of his new work Egdon Heath. This was to be his last appearance before the Cheltenham public. When Gustav died in May 1934 the Holst family had been an adornment of the music life of the town for the best part of a century and their lasting legacy is the sustained fame of the music that one its own has left to music lovers worldwide. Even then there was to be one more generation of the Holst family contributing to the musical heritage of the town. Gustav’s daughter, Imogen, a composer in her own right, actively encouraged and contributed to the opening of the Holst Birthplace Museum in 1975 and when Sir Mark Elder unveiled a statue of Gustav Holst in Imperial Square in 2008 Cheltenham had another permanent reminder of the man, his music and the musically talented family of which he was an eminent part.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the encouragement and advice of Laura Kinnear, Curator, and Steven Blake, trustee, at the Holst Birthplace Museum and to Helen Brown and Ann- Rachael Harwood at Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum for their help in relation to the images shown here

References

1 For a comprehensive summary of the Holst family see the introductory article to the catalogue Theodor von Holst His Art and the Pre-Raphaelites – an exhibition of paintings and drawings by Theodor von Holst, son of Matthias, in the Holst Birthplace Museum in September 2010. The article is written by Laura Kinnear, Curator of the Museum.

2 Hogwood, C., Haydn’s Visits to England, Thames & Hudson, 2009, p107

3 Cheltenham Looker-On ( hereafter CLO) September 11 1840

4 The advertisement appeared in the CLO on November 27 1841 and the review on December 4.

5 CLO December 4th 1841

6 The first prospectus for ‘The Cheltenham College Institution for the Education of Young Ladies’ was published in the CLO of November 12 1853. It included Herr Gustavus von Holst among the list of Professors. Music was a mong the regular courses on offer but extra lessons were available at 5 guineas per half -year session.

7 CLO October 9 1852

8 CLO December 12 1863

9 These two concerts were reviewed in CLO on February 27 1864 and February 10 1866.

10 Holst,Imogen, Gustav Holst A Biography, Oxford University Press, Second edition, 1988, p 5

11 CLO January 11th 1892. The reviewer also noted that this was the first time this number had been performed in Cheltenham.

12 Holst ,I., Ibid, p 6

13 CLO December 13th 1890

14 Short, M. Gustav Holst The Man and his Music, Oxford University Press ,1990. On p 13 Short records that young Gustav played Mayer’s La Fontaine, as a solo, a Grieg piano duet and movements from a piano quintet by A Burnett.

15 Gibbs, A., Holst Among Friends, Thames Publishing, .2000, Second edition p16 Gibbs records that Gustav stayed in Oxford with his grandmother while studying with George F Sims, organist at Merton College and St. Philip and St. James

16 Ibid, p 10

17 Holst, i., A Thematic catalogue of Gustav Holst’s Music, Faber Music limited, 1974 p 6

18 CLO May 4th 1895

19 CLO October 10th 1896

20 From the All Saints ‘ Parish Magazine for September 1895 as quoted by Lowinger Maddison in The new All Saints’organ, June 1887 (Cheltenham Local History Society Journal 5).

21 Short, M., ibid. p14