Tom Clarke, © 2014

For a man with socialist sympathies, and famed for his simple and modest life, it is ironic that Gustav Holst once gained support from Rolls-Royce, the very epitome of luxury and exclusiveness. But there was a human side to this story that probably accounts for Holst moving within this circle for a few years. His contact with Rolls-Royce involved someone like himself who preferred to keep out of the limelight.

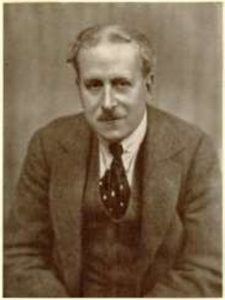

The Commercial Managing Director of Rolls-Royce Ltd. from 1906, and soon its full managing director, was Claude Goodman Johnson (1864-1926), a man of liberal outlook. He was one of seven children, born to a religious father who worked first in the glove trade and then at the South Kensington Museum, teaching himself much about art for self improvement. He instilled a love of church music and Bach into his children. Of Claude’s brothers, Cyril Leslie became a composer, Douglas a Canon of Manchester cathedral, and Basil succeeded him briefly at Rolls- Royce Ltd. Although not artistic Claude had a deep feeling for art and music.

Claude Johnson was undoubtedly the business force which made Rolls-Royce preeminent in the Edwardian period and beyond. His organisational skills were phenomenal. As soon as he had Rolls-Royce on a sound footing he began to seek out artists who could enhance the Rolls-Royce image. He used the great sculptor and typographer Eric Gill in 1906 to design the company’s font. The sculptor Charles Robinson Sykes was invited to design the company’s famous car mascot, the Spirit of Ecstasy, in 1910. His best friends were the portraitist Ambrose McEvoy, who went on to do stylish advertisements for the company (and whose paintings Johnson catalogued in a private publication), and Sir James M. Barrie the celebrated children’s author. He was also friendly with the newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe, with Rudyard Kipling, the artist Augustus John, and the sculptor F. Derwent Wood.

In 1916 Johnson moved permanently to a lovely seaside villa at Kingsdown in Kent, named ‘Villa Vita’ by its builder in the 1870s, Lord Granville. Johnson had bought it in 1913 to be closer to both Henry Royce living at St. Margaret’s at Cliffe and to Northcliffe’s seaside weekend home ‘Elmwood’ in Thanet. It was here that Johnson’s patronage developed further.

By 1919 Johnson had two daughters (the first by his recently-deceased wife) and a very young new wife, nicknamed ‘Mrs Wigs’. He was also comfortably off, as the building in 1911 of a villa at Le Canadel on the French Mediterranean coast attests. In addition, he had a Rolls-Royce fund at his disposal to use at his discretion for promotional purposes. Some of this no doubt supported his lavish European travels. Perhaps the most public patronage he gave was to Marcel Dupré (1886-1971), organist at Notre Dame in Paris, whose improvisations he had heard for the first time at the cathedral on 15 August 1919. Starting that year, he placed company cars and travel costs at Dupré’s disposal as well as fitting the organ of Notre Dame (and later St. Sulpice) with electric blowers at Rolls-Royce expense. Dupré played for Johnson during a stay at ‘Villa Vita’ in September 1920. By far the greatest event Johnson organised was a Dupré concert at the Albert Hall on 9 December 1920 in the presence of the Prince of Wales and other royalty, financially supported by Lord Northcliffe. Dupré returned in May 1921 to give concerts around Britain.

There were many others famous in the musical and art worlds whom Johnson cultivated and entertained at his country home, such as the opera singer Dame Nellie Melba and caricaturist Max Beerbohm. More direct support concerned Capt. Francis Burgess (1879-1948) whom Johnson had known before meeting Dupré. Knowing how important Burgess’s work in the Gregorian Society was, Johnson supported him by the simple expedient of creating a notional ‘job’ for him in the aero publicity section at the Rolls-Royce offices in London, purely so that funding could be channelled into Burgess’s scholarly work on plain chant and into books about the organ.

Johnson was also moved by Claude Debussy’s music and knew of Cortot’s study on the composer but as far as is known no patronage was given to Debussy. But Johnson did become friendly with George Copeland (1882-1971), the American pianist and interpreter of Debussy who stayed at ‘Villa Vita’ during February to April 1921. For Holst, however, Johnson had such high regard that it is claimed he offered to pay for a festival of his music. Michael Short’s Holst biography describes how Holst instead accepted £1,500 to enable him to compose free of other concerns. (Imogen Holst described it as ‘several hundred pounds’.) Today that £1,500 would be worth £80,000 after allowing for inflation. It is said that Johnson warmed to Holst’s music after hearing The Perfect Fool (performed at Covent Garden on 15 May 1923) but Johnson would already have known The Planets, if not other pieces. Luckily, Johnson’s diary yields more information: 28 June 1923 refers to his connection with the composer, noting ‘Savitri & Perfect Fool at opera. Capell to lunch to discuss Holst concerts in autumn. CJ undertook to guarantee financial results.’ (Richard Capell 1885-1954, a

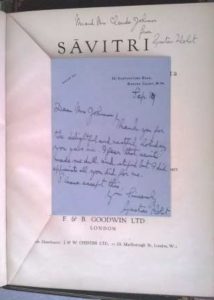

music critic who often reviewed Holst’s works.) This acquaintanceship with Johnson occurred whilst Holst was based at Thaxted in Essex. Some of the information about this period is, however, anecdotal and came from Holst’s daughter Imogen and her contact with Holst’s biographer. On 19 September 1923, writing from his assistant Miss Vally Lasker’s London address, Holst sent the Johnsons an inscribed copy of the newly-printed score of ‘Savitri’. This was to thank them for a short holiday he had enjoyed with them at ‘Villa Vita’. As usual, CJ had this beautifully rebound for Evelyn’s library at the house.

The help for Holst from CJ was not anonymous or indicative of an arm’s length relationship. From notes found in the diaries of Johnson’s daughter, Mrs. Joan ‘Tink’ Riddle, it is clear that Holst (but perhaps not his wife Isobel, or Imogen) enjoyed further time with the Johnsons at ‘Villa Vita’. The entry for 3 July 1925, for example, referred to Holst, Johnson, and Johnson’s Airedale terrier Jack going to ‘Villa Vita’ from London – Johnson had apartment 3 in The Adelphi on the Strand, next to J. M. Barrie. The next day Holst walked to St. Margaret’s Bay whilst in the evening Holst and Mrs. Johnson went to Canterbury. On Sunday 5 July 1925 Holst and Johnson returned to London by train where Holst went walking and got wet! Holst returned to ‘Villa Vita’ on the Monday night. All of this was just two days prior to Johnson’s new 48 ft launch, ‘Vita’, being named and so some jaunt at sea could have happened whilst Holst was a guest. Holst was in Kent in December 1925 which possibly means ‘Villa Vita’ once more. At the very least this sociable time implies friendly relations between Holst and the Johnsons during 1924-25. Holst would have enjoyed Johnson’s cultured milieu as well as his impish humour.

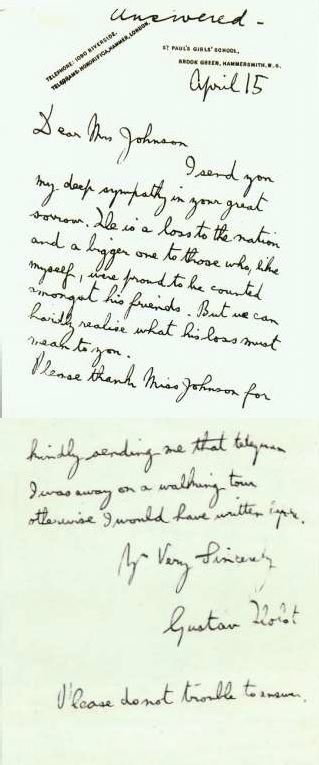

Johnson died suddenly of pneumonia on 11 April 1926 and Holst’s sympathy note to Mrs. Johnson survives as a final reminder of Holst’s short time in a Rolls-Royce circle.

Tailpiece:

Interestingly, there was an even earlier association between a member of the von Holst family and the family of the Rolls-Royce co-founder, the Hon. Charles Stewart Rolls (1877-1910). Gustav Holst’s great-uncle Theodor von Holst (1810-44), a painter of some reputation in the early Victorian period, was taken up by the wealthy John Etherington Welch Rolls (1807-70) of ‘The Hendre’ at Rockfield near Monmouth. John Rolls was C. S. Rolls’s grandfather and collected at least five von Holst’s works, commissioning a portrait of his sister Jessy, Mrs. George Simon Harcourt, in 1837 and buying at an 1844 auction a large collection of about 300 von Holst drawings. These drawings forming the leatherbound ‘Rolls album’ only left the Rolls family when the contents of ‘South Lodge’ in Knightsbridge and ‘The Hendre’ were auctioned during 1959-62. The album was subsequently broken up. Until then C. S. Rolls’s sister Eleanor, the Hon. Lady Shelley-Rolls (1872-1961, wife of Sir John Shelley, Bt., later Shelley-Rolls), owned the family estates. The Rolls barony of Llangattock became extinct in 1916 because the heir, C. S. Rolls’s brother John Maclean 2nd Baron, was killed in France and a third brother, Henry Allen, died earlier in 1916 for reasons unconnected to the war. Charles Rolls would, therefore, have been familiar with von Holst’s works on the walls of ‘The Hendre’ and the family’s London home ‘South Lodge’.

Sources: Organists’ Review May 2004 p.123-129 for Dupré and Johnson by Prof. Tom Murray; Michael Short Gustav Holst: the man and his music (1990) p.217 and Michael Short Gustav Holst: letters to W. G. Whittaker (1974); Imogen Holst Gustav Holst: a biography 2nd ed (1969) p.89; Wilton J. Oldham The hyphen in Rolls-Royce: the story of Claude Johnson (1967); Rolls-Royce Enthusiasts’ Club Bulletin no.276 p.44-5, no.280 p.30-2, no.322 p.27-9 for Holst references.

My thanks to Michael Short and Alan Gibbs for checking some aspects for me; and to Max Browne for generous assistance with the added section on Theodore von Holst. Copies of the 1994 exhibition catalogue (150 years after the death of Theodor von Holst) and the 2010 exhibition catalogue (bi-centenary of his birth) are available from the Holst Birthplace Museum.